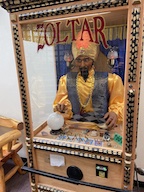

A couple of times a year when passing through New Mexico, I am accosted by Zoltar, who would like to help me. I have yet to consult him, however, as I am generally en route elsewhere. But I appreciate his interest. If you ever watched the 1988 film BIG, you know something of Zoltar’s persuasive power and how it worked on the very young Tom Hanks.

If you saw the film, you also know that Zoltar is an automaton who will respond to your interest only when fed a bit of money. But he also has a face and some rather distinctive garb, differentiating him from the other automata in my life; you probably know them, too: one lives inside my mobile phone and the other occupies a kind of hockey puck-ish thing in the living room.

Before there were ChatGPT and its ilk, there were gadgets that would do things for you on command (or for just the insertion of a coin or two). For a decade or so the ones in the phone and the puck (why didn’t Amazon go all Shakespeare and name theirs after the magical chap who facilitates such a happy resolution to A Midsummer Night’s Dream?) have been introducing us to something that passes for artificial intelligence.

That’s a heck of a circuitous prologue to this post about the ways in which institutions of learning of all kinds seem to be approaching, under serious time pressure, the advent of AI—two letters that seem to be striking more fear than wonderment or hope into educators everywhere.

Mostly we seem to be past the absolute handwringing stage, at least inside our schools and universities. We haven’t completely escaped the choruses of “They’re all gonna cheat! They’ll never learn to write!”, and those messages are being gleefully reiterated and even confirmed at every turn. But the rule-cravers have been busily trying to find language that encompasses and condemns all the ways in which AI can be used in pursuit of devious ends.

And no doubt AI users, even those of less devious dispositions, have been looking for loopholes and workarounds for each new rule with equal or greater fervor. What’s a school to do?

Hard and fast rules may appeal to those who like to see the world in moral binaries: right/wrong, honest/dishonest, good/evil. But rules are only rules, and as long as there have been reflective humans, there have been reasonable doubts about such binaries, based on situations and experience every bit as much as on “what the handbook says.” A school is not just an intersection with a stoplight but a decision-making maelstrom, and humans tend to arrive at important truths most confidently by discussion, reflection, and the sharing and even debating of ideas and perspectives; rulebooks are only ever a starting point.

And of course the rule-and-policy movement starts with an a priori assumption about artificial intelligence engines that is itself rather limited in perspective. In the most pessimistic view, AI is simply a clever tool for cutting corners that will lead us, inevitably, down the path to the destruction not just of our students’ (and our own?) moral agency but of humanity itself.

But for every article and listserv post I have run across that decries AI as a “problem,” I am reading others that offer examples of and ideas about using AI to deepen understanding and add really useful nuance—along with access to mountains of research and other evidence—to instruction. As with smartphones and Wikipedia in times not so long ago, technologies like ChatGPT can in fact be used to good ends, as long as all users—students and teachers alike—understand and acknowledge these technologies’ limitations.

Lately I have been deluged with shared “AI policies,” though I confess I have not read them all in detail. What I hope most fervently, and what I earnestly hope will come out of the ongoing discussions of such rules and policies, is that these discussions are not being held only in the offices of the final arbiters of each school’s rules and policies but are in fact emanating from—and can evolve based on the experiences of—the classroom experts (I call them teachers) in whose milieus AI will likely become a ubiquitous presence.

Whether this presence is ultimately benign or malevolent will have a great deal to do with how we all learn—all of us, together—to harness and adapt artificial intelligence to the purposes of our classrooms, the needs and interests of our students, and the values and missions of our schools.

An old professor of mine once penned a study titled Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human that dissects in detail the ways in which The Bard’s works illuminate a vast range of human emotions, behaviors, and morality. Perhaps the people who named Google’s AI engine Bard were onto something: clever, fast answers are surely gratifying, but as we become more adept at applying artificial intelligence, perhaps what we can learn about ourselves and how we think, feel, make decisions, and act out our values will be the true benefit of this powerful technology.

So, may our rules and policies reflect not just our trepidations and anxieties but also the best of our deepest selves, intentions, and human aspirations. I know this is what Siri, Alexa, and Zoltar would want for us.